Domestic cats, now ubiquitous in homes and popular culture, have long been difficult to trace genetically due to a lack of clearly interpretable archaeological evidence. For years, the prevailing theory was that cat domestication began around 9,500 years ago in the Levant, at the beginning of the Neolithic period, when humans began to cultivate and store grains. These reserves attracted rodents, and wild cats would naturally have followed, giving rise to a coexistence that would have gradually led to domestication. However, a new series of studies based on ancient DNA analysis is turning this narrative on its head. This research, conducted by an international team and published in Science and Cell Genomics, shows that the situation is more complex and that the domestic cats present in early agricultural societies were probably not the genetic ancestors of the cats we know today.

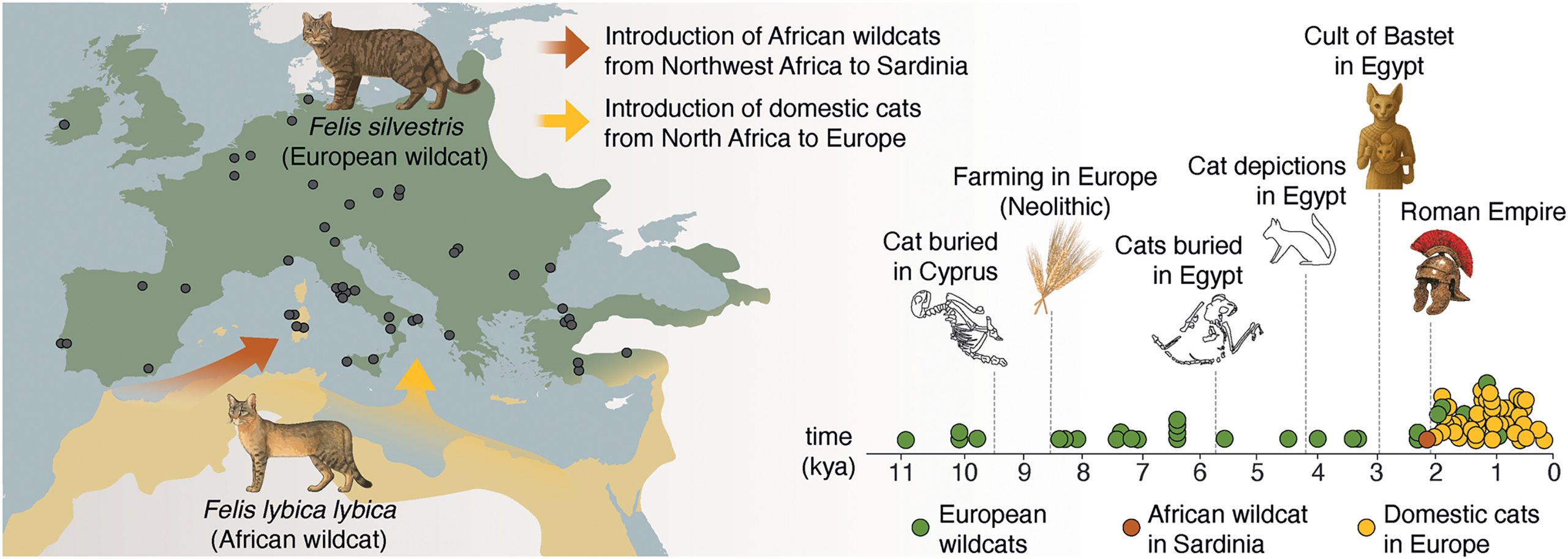

The first study by M. De Martino et al. published in Science examined 87 ancient and modern cat genomes in North Africa and Europe. It shows that the true domestic cat (Felis catus) did not originate in the Levant but in North Africa, where its close relative, the African wildcat (Felis lybica lybica), lived. This group is believed to have formed the genetic basis of the modern domestic cat and spread to Europe during the expansion of the Roman Empire around 2,000 years ago. This means that cats living alongside humans before this period did not belong to this domestic lineage, even though their appearance may have been very similar.

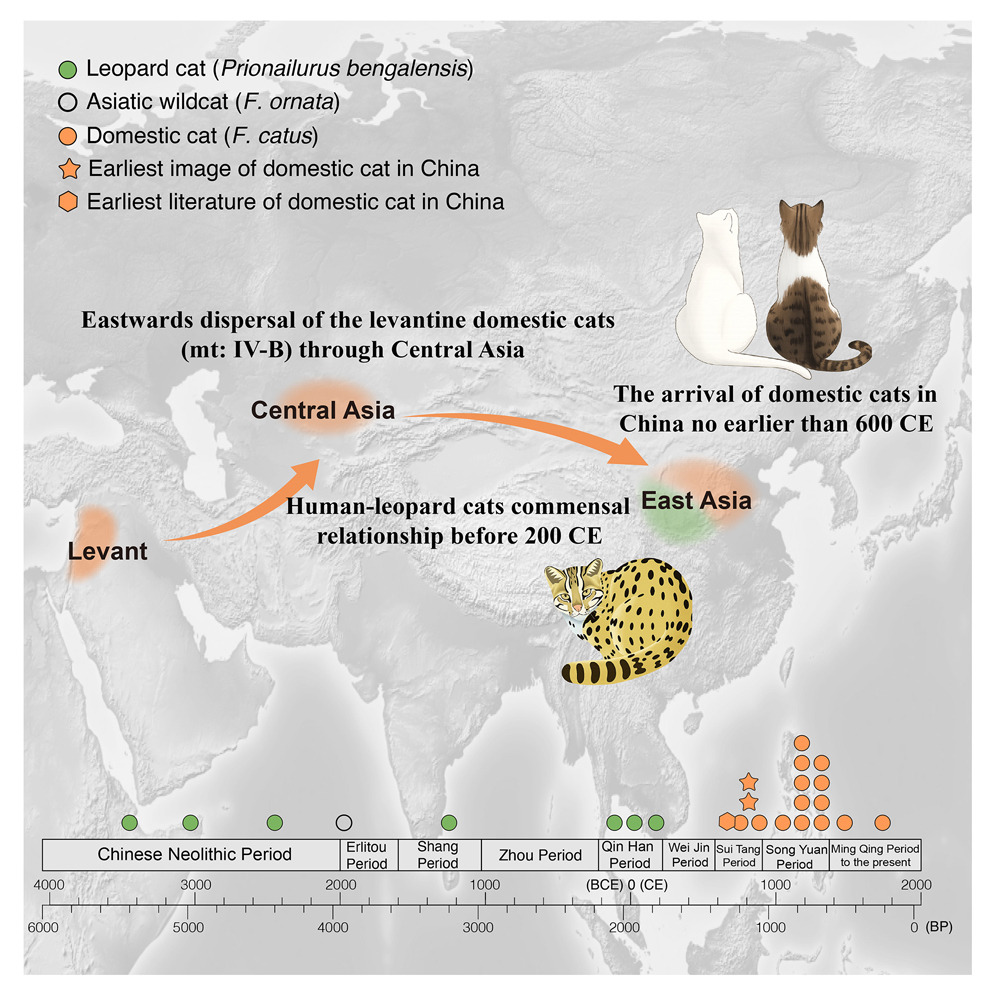

The second study by Yu Han et al., published in Cell Genetics, makes an even more surprising point: before the arrival of the modern domestic cat, another feline had already been living alongside human communities in regions close to China for thousands of years. This was the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis), a wild Asian species that does not naturally hybridize with cats of the Felis genus. DNA analyses carried out on 22 bones dating back 5,000 years revealed that this feline cohabited with humans between 5,400 BCE and around 150 CE. However, this cohabitation was of a “commensal” nature: the leopard cat benefited from the rodents attracted by human activity, while humans benefited indirectly from its presence. It was not domesticated in the strict sense, as there is no evidence of selection, human control, or behavioral evolution comparable to that of the domestic cat. Archaeological remains show that these felines lived in or near human settlements, but without developing a stable relationship such as that later observed with Felis catus.

Several factors explain why the leopard cat was never domesticated, despite more than 3,500 years of cohabitation. On the one hand, it is known for its tendency to attack chickens, which has earned it the folkloric nickname “chicken-catching tiger.” With the evolution of agricultural practices after the Han dynasty, from free-range farming to cage systems, conflicts between humans and leopard cats probably increased, making them undesirable in villages. At the same time, climatic and social changes, including a colder and drier period, transformed agricultural landscapes and reduced the ecological niches available near human settlements. These conditions drove the leopard cat back to its natural forest habitats, where it still exists today.

These recent discoveries have reignited the debate about the role of ancient Egypt in the history of domestic cats. Depictions of cats in Egyptian tombs show animals integrated into family life, wearing jewelry or sharing meals. However, it is unclear whether Egypt was the actual site of domestication or simply an important center where cats that were already commensals became companions. Despite these advances, researchers emphasize that the history of cats remains incomplete. Samples from North Africa and West Asia are still needed to better understand how Felis catus, our beloved everyday companion, spread.